Notes Toward Day 17: Film’s Expansiveness and Limitations

Live Blogging the conversation…

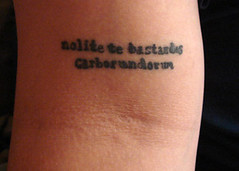

Images of us @ work….

- Image by kawaface via Flickr

First, a personal story about the film version of “The Handmaid’s Tale“: it was the first movie Doug and I watched together, not exactly the kind of thing that might inspire young love. We’ve always liked unusual films, though, so it fit. I saw the film almost 20 years ago. At that time, I had not read the novel. What I remembered of the film were the ceremony scenes and the ending when the Commander is killed and Offred ends up in a rundown trailer in the mountains of Canada. I think it’s an okay film, not the worst thing I’ve ever seen but not the best. What I find most intriguing is how the book gives a certain impression of the main character as someone enduring a terrible situation, as someone suffering mostly internally (and I’d say this is true of many of the characters) while the film externalizes those conflicts and that suffering in a way I didn’t think the book did. Mechanized humans is really what I think of when I think of the characters in the book. The film misses lots of the subtle nature of oppression, how it sneaks up on us sometimes rather than coming all at once, and the ways in which we might be complicit in that oppression simply out of a need for survival.

Whatever we think of the film, it does provide us with some interesting food for thought. It made me intensely curious about how the film was made and what those makers thought of the film. Here is the director, in an interview, suggesting the film was not important to him:

I always had a problem with “The Handmaid’s Tale” (his 1990 cautionary film about near-future totalitarianism) and I kind of divorced myself from that movie because I never really bought the premise. I always thought this would never happen, not in this country. Now, Oklahoma.

I find it intriguing that Atwood wrote the book as a cautionary tale, suggesting what might happen to our society and that Schlondorff dismisses that caution, thinking “this would never happen.”

Natasha Richardson, who played Offred, had issues with the screenplay and the film’s production:

But she also made it clear that her loyalty was to Canada’s Margaret Atwood, rather than the movie, and she took delight in chastising the big Hollywood studios which had refused to finance a feminist-oriented story that was clearly set in a United States taken over by right-wing fundamentalist fanatics – a country where the few remaining fertile women were required to act as surrogate mothers or “handmaids” to the ruling male elite.

It was her concern for the integrity of Atwood’s novel which led to her bold criticism of Pinter’s screenplay. The irony was that Atwood had initially given a screen version the nod because Britain’s greatest living playwright would do the adaptation.

Richardson recognized early on the difficulties in making a film out of a book which was “so much a one-woman interior monologue” and with the challenge of playing a woman unable to convey her feelings to the world about her, but who must make them evident to the audience watching the movie.

She thought the passages of voice-over narration in the original screenplay would solve the problem, but then Pinter changed his mind and Richardson felt she had been cast adrift. (http://www2.canada.com/topics/entertainment/story.html?id=1402532)

Pamela Cooper writes about the differences between the two versions, particularly about the way the film refuses some of the complications of the relationship between the reader and the text, or in this case, the viewer and the film.

If Offred can murder her Commander and escape, pregnant with Nick’s child, to a pastoral haven to await the birth in a state of mild, contented boredom, then totalitarianism as the film presents it is a fragile political structure, relatively easy to assault, overcome, and evade. The historical experience of totalitarian regimes in the 20th century deeply contradicts this implied view–and its sentimentality undermines not only the political analysis, but the moral unease and didactic fervor of Atwood’s novel. To depict Offred, as Schlondorff and Pinter do at the end of the film, as a comparatively happy, reasonably safe, and definitely expectant mother–an Offred unconvincingly transformed from parodic to actual Madonna–is to draw the teeth of Atwood’s satire. The film’s soap-opera conclusion demeans the power of The Handmaid’s Tale as a moral warning based not on fantasy, but on the vicious realities of postmodern politics. It weakens the literary authority of the novel as a cautionary tale in the Swiftian tradition of outraged social responsibility–a legacy of satirical pessimism which Atwood deliberately claims for her text by taking one of its epigraphs from “A Modest Proposal.”

The omission in the film version of the novel’s framing device, “The Historical Notes on The Handmaid’s Tale,” suggests another opportunity for ironic awareness lost to the movie. Given Pinter’s experience with self-conscious narrative techniques–he and Karel Reiss developed an effective cinematic equivalent for John Fowles’s metafictional strategies in the film of The French Lieutenant’s Woman–the exclusion of this discursive dimension is even more keenly felt. It is in this fictive appendix that the novel cynically affirms the continuing prevalence, in a mythical 22nd century, of the surveying and ordering male authority so entrenched during the Gilead era. The editor of the tapes constituting the document known as “The Handmaid’s Tale”–the controller and interpreter of Offred’s recorded experience–is yet another doctor: the smug Professor James Darcy Pieixoto represents an academic establishment now reconstituted along the lines of apparent gender equality, but effectively still male dominated. With the lethal political ironies of the post-Gilead world unrecorded in the film, there is nothing to challenge the facile assumption focalized in its conclusion: that the punitive mechanisms of surveillance represented in the novel can be evaded–that there are places safely unreachable by the Cerberean Eyes of Gilead.

The whole artcile is worth reading. Cooper, Pamela. . “Sexual surveillance and medical authority in two versions of The Handmaid’s Tale. ” Journal of Popular Culture 28.4 (1995): 49. Research Library. ProQuest. Bryn Mawr College Library, Bryn Mawr, PA. 24 Mar. 2009 <http://www.proquest.com.proxy.brynmawr.edu/>

What interests me are the gaps, additions, and modifications made to the story for the film version and how those affect the message of the novel. So, I want to start today by briefly examining the key moments for you that positively or negatively affect your perception of what Atwood was trying to get across in her novel.

Second, I want us to try to construct a different version of the film. We won’t have time for a full-blown scirpt, but I’d like to consider several other elements and at the end of our time, have an elevator version of the story and a generally fully storyboarded film (these can be stickfigures for all I care). From WikiHow’s “How to Make a Movie,” here are some elements to consider and to have answers to:

1. What type of movie will you make: documentary, narrative, art film, animation? Think about the variety of genres we came up with for the book. Also think about how you might deliver the film. Should it be a full-blown, released at a film festival or for a movie theater film? Or should it be released on the web or in some other way?

2. Create a script and storyboard it. We don’t have time for a full-blown script, but try to jot down the scenes you want to include and in what order and sketch those out in storyboard fashion.

3. Casting–who would you cast for the film?

4. Where would you film it and what would the setting look like?

5. Costumes. What do the characters dress like?

Come up with the elevator speech, the 30-60 second spiel that you give to the movie executive while riding up on the elevator with her.

I want us to try to think about the reasons for constructing the film the way we do.

Finally, here’s an interview Bill Moyers conducted with Atwood on the novel:

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1466c105-9c0c-4388-addc-a9f3468077bd)