Skinny Tights and High Heels

Gender and Technology

Anne Dalke and Laura Blankenship

March 6, 2009

Skinny Tights and High Heels

Fashion as a Lens for the Technology of Gender

.

Michelle Obama walks down the paved street beside her husband at the presidential inauguration, waving to people lined up in the frigid air to welcome and in turn be welcomed by the couple which will head a new administration in Washington. M. Obama wears a lime-yellow Isabel Toledo outfit, transforming, as one headline puts it “lemongrass [into] the new black”[1]. The sparkly, almost golden dress matches her green J. Crew gloves and Jimmy Choo shoes. But wait. Why are we talking about M. Obama’s clothing? Who cares? What does that have to do with how good of a first lady she will make? Did you ever hear anyone talking about Bill Clinton’s attire at a Hilary Clinton rally? I didn’t, though I heard an awful lot about H. Clinton’s fashion styles.

.

We can think of clothing as a kind of technology. Both the physical material of it and the construction and organization of an outfit may be “artfully crafted”. Then again, they may just be thrown together, but that itself is a construction of sorts. So how do people engender the technology of clothing? By this I mean how do they genderize or make gendered the construction of wearing clothes – not how they produce this technology and further it.

.

I seek to explore three different facets of the interaction between fashion as a medium that relates to the intersection of gender and technology. First I explain a conceptualization of the system and technology of gender and illustrate it with the example of the technology of fashion. I argue that by wearing gendered clothing (where clothing itself is a technology), we perpetuate the technology of gender stereotypes (and of gendering clothing). Second I look at how marked clothing is gendered and how this contributes to the construction or technology of gender. Finally, I notice how, in relation to fashion (as well as profession), the technology of gender is a system that is in gradual flux. So, my point is that the technology of gendered fashion is an instance of a system that reproduces gender stereotypes, but that this system changes over time.

.

.

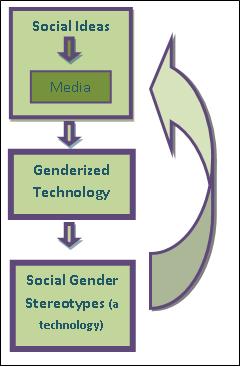

Gendering Technology, Gendering Ourselves

As I said in class, society, with the helping filter of media, engenders fashion, as it engenders many other technologies. Since I like the input-output charts I made last time, I am adding one to this paper too, for the purpose of illustrating my point. This process, represented in Figure 1, first takes social ideas to produce genderized technology. In the fashion example, people select, buy, and wear clothing originally manufactured by fashion designers (the media). Most often, women typically wear “female” clothing (where “female clothing” is a nebulous labeler determined by the culture and time period) and men wear typically “male” clothing, hence gendering the technology of clothing.[2] After using social ideas to create genderized technology, this technology perpetuates the social gender standards – which are, as I have just described, a construction or technology . Hence women wearing “female” clothing and men wearing “male” clothing perpetuates a constructed difference in the appearance of people. In other words, the genderized technology itself furthers (engenders!) social gender stereotypes.

.

I want to make a note about the gendering of technology here. While fashion certainly seems to apply to the diagram in Figure 1, as do a number of other technologies (perhaps even some webpages themselves, to brashly refer to myself…), I wouldn’t say technologies are always gendered – though many are – nor are they inherently gendered (except maybe the technology/construction of gender itself…. Could that not be gendered? . In some sense, clothing at its most basic level is not inherently gendered, since it is simply fabric and material used to clothe a person. However, in most and perhaps all cultures, the creation of this craft has historically gendered clothing and currently genders it. As I said above, however, not all technologies/crafts are gendered. For instance, basket-weaving or pottery-mug creation, which basket weavers and potters create without the gender of the consumer or user in mind. We do not generally have gendered coffee mugs (though yes, I’m sure there are some) in the way that we do generally have gendered clothing.

.

Figure 1. Gender and Technology as an Eternal Feedback Loop. Ideas currently operating in society are filtered through the media to result in a genderized image of technology. This technology then perpetuates social gender stereotypes (which are themselves a technology of sorts), which then feed back into societal ideas and ideals.

Perhaps the difference is that we use coffee mugs as ends in themselves, as useful, drinkable containers, whereas we self-present ourselves to others, we perform ourselves, and communicate ourselves to the world and society by means of our clothing. Further, clothing rests against our bodies, and hence begins to become part of our identity (how we see and express ourselves) as well as our affinity (how we work within our community on a smaller scale and society on a larger scale), rather than the more external coffee mug.

.

.

Marking Clothing as a Technology of Gender

We can think of self-presenting through our clothing as a way of being marked and marking ourselves. Self-presenting and marking ourselves lends us agency, whereas being marked extracts our agency, re-positioning it on those others, the society who marks us and judges us. In “Marked Women”, Deborah Tannen notices how we mark ourselves with our clothing, and she states that women, in particular business women, cannot escape marking, whereas men can. In the context of a (presumably American) business meeting, she observes the clothing of the women and men, noticing that while the men could have been marked (by wearing sandals not business shoes or sporting “oily longish hair falling into eyes” not short, parted plain haircuts), they chose not to be. For the women, she says, there is no choice: “I asked myself what style we women could have adopted that would have been unmarked, like the men’s. The answer was none. There is no unmarked woman” [my emphasis][3]. She hypothesizes that, at least for businesspeople in America in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the craft or technology of clothing-wearing gives men a choice to mark themselves or not, but mandates that women must mark themselves[4][5]. Generally, that women and men can mark themselves and that women must be marked relates back to the original concept shown in Figure 1: by marking ourselves with the genderized technology of clothing, we continue the cycle of societal gender standards.

.

Interestingly, the repercussions of this idea are not necessarily entirely a benefit to men. While having the choice to mark or not mark oneself would seem to engender freedom. However, by having a default, unmarked option available, it may make it harder to choose a non-default option – in other words, not to conform. On the one hand we can say, for example, “Have you ever seen an unmarked female politician?” or, “When have you noticed a female politician’s clothing not being remarked upon in some media (newspaper, blog, news station)?” and the answers would be “not often” or “never”. On the flip side, though, we could say, “When have you seen a male politician in marked clothing?” and you would likely say “not often”.

.

So on the one hand, women’s marked clothing will likely be noticed and/or discussed. In other words, it is a technology that is explicitly reinforced, marked, discussed in society. On the other hand, this encourages a diversity of clothing expression within the women’s community which is lacking in the men’s community. In a way, the lack of a default women’s clothing urges women to expand norms (the norm is to express oneself) – though at the same time, within the range of clothing certain genres have come to be more or less accepted and certain genres have come to gain particular significance. For example, Tannen describes how the way in which a woman dresses herself signifies something about herself: “If a woman’s clothing is tight or revealing (in other words, sexy), it sends a message – an intended one of wanting to be attractive, but also possibly unintended one of availability. If her clothes are not sexy, that too sends a message, lent meaning by the knowledge that they could have been”[6]. Hence whether intentionally or not, women’s marked clothing communicates something about her sexual status as well as other traits of hers. More broadly, the interaction that society has with men versus women in respect to their clothing – noting women’s marked clothing, explicitly reinforcing their technology and largely ignoring men’s often unmarked clothing, implicitly reinforcing the technology of male clothing – contribute to an overarching technology of gendered clothing.

.

.

Changing the Technology of Gender

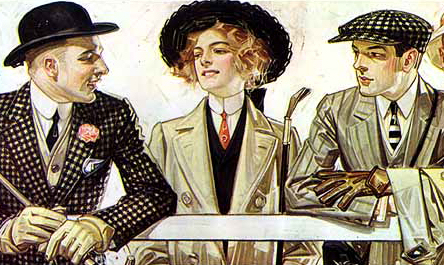

Finally, I wanted to briefly mention an interesting phenomenon I have been noticing in fashion styles which brings up a hypothesis for the construction/technology of gender more generally. On a historical (and cross-cultural) level, the technology of gendered fashion has changed dramatically. For instance, see Figure 2, which shows a man (Henry VIII, in fact) who wore jeweled, fancy clothing. I also came across the image from Figure 3, which is an advertisement for Arrow shirt collars. Interestingly, the attire of the woman in the center of the picture is strikingly similar to that of the men’s – the only major difference I could spot was the style of her hat. The purpose here was likely to sell Arrow shirts to a wider audience. This makes it all the more interesting, since so often advertisers are reinforcing gender stereotypes (playing into the feedback loop of Figure 1 by playing the part of the Media).

.

|

Figure 2. Henry VIII in Fancy, Jeweled Clothing.

|

In the way that fashion has changed historically, it mirrors how the technology of gendered professions has changed greatly over time (as well as across cultures). For one example, male nurses used to be quite abundant, while now they are scarce. Women medicinal healers were popular until schools of medicine opened and barred their doors to women, after which men were more predominant in the field. Geishas in some ways uphold current gender expectations of female performance and wo

Figure 3. Arrow Collared Shirts Advertisement. The woman in the center looks strikingly similar in attire (with the exception of her hat) to the men on either side.

men as beauty objects. However, their role also encompasses the thinking up of witty remarks and entertaining an influential man, a role not unlike that of the traditional male court jester for the king.

.

|

Figure 3. Arrow Collared Shirts Advertisement. The woman in the center looks strikingly similar in attire (with the exception of her hat) to the men on either side.

|

Both of these observations seem to be part of a larger social system whereby the construction/technology of gender itself changes across time. In one sense, we see fashion changes all the time; new fads brim up each month. However, being humans living on a limited time scope, we don’t see the larger changes that occur on a much broader time scale. We, by which I mean Americans living in the 20th/21st century, still see women dressed pretty, women dressed sexy, and women as objects . In the past, though, men wore fancy clothes too, and the fashion of skinny pants for women which we sometimes (if we’re not reflecting too much about those images of men in skinny tights with funny hats) think of as unchanging has changed a lot.

.

So how does this observation then modify our original Figure 1, the image of gender as a self-perpetuating technology? Some other forces are shaping this technology, since by the above observation, the technology indeed is changing, slowly, over time (much like the idea of evolution in biology). So who or what is changing it? Perhaps on an individual and collective level, by gradually altering how we mark ourselves, how we self-present, we change the system. Perhaps we ourselves have the power to change this grand old structure, this system and technology of gender that affects everything from the ties we wear, the old tshirts we sport, right on down to the shiny high-heeled shoes we wear.

.

Images

- “File:Holbein henry8 full length.jpg. Wikipedia.” <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Holbein_henry8_full_length.jpg>. 05 Mar 2009.

- “File:Leyendecker arrow color 1907 detail.jpg.” Wikipedia. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Leyendecker_arrow_color_1907_detail.jpg>. 05 Mar 2009.

[1] Mata, Brenda Brissette. “Michelle Obama inaugural day dress makes lemongrass the new black.” 22 Jan 2009. The Flint Journal. <http://blog.mlive.com/flintjournal/bmata/2009/01/michelle_obama_inaugural_day_d.html>. 04 Mar 2009.

[2] I realize that some people may not identify as strictly female or male, that some may self-identify in a way that contradicts what others label them, and that not all other/female/male-gendered people who do perpetuate clothing (or other) gender stereotypes. I think these are interesting and useful decisions. However, it is outside the scope of my chosen essay topic to delve into these ideas, so for ease of discussion I will refer to people as either male or female (regretfully, reinforcing the binary myself).

[3] Tannen, Deborah. “Marked Women.” Reading Critically, Writing Well. Ed. Axelrod, Rise B., Charles R. Cooper, Alison M. Warriner. pp. 232-237. <http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=JQQoe7giCbUC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=clothing+%22michelle+obama%22&ots=QVkNEr1stO&sig=GGql9uekcdIv8qz9bOHrv7YFa7M#PPA237,M1>. 05 Mar 2009.

[4] I would not claim that this is as much the case in younger people’s casual clothing. For instance, based on my experience in high school, wearing a pretty but pretty ordinary Gap shirt and jeans pants would probably be default young women’s clothing, and wearing a t-shirt and jeans would probably be default young men’s clothing.

[5] She also cites The Sociolinguistics of Language , where author Ralph Fasold discusses how in terms of chromosomes, the unmarked version is XX rather than XY, the former (usually) signifying a female person. Hence if we left up the decision of marking human clothing up to the biology of chromosomes, women would be unmarked and men marked (also, differently from our society’s construction of gendered clothing, neither gender would have the choice of being, respectively, marked or unmarked). Interestingly, scientists will sometimes say that women are the “default” whereas Tannen never uses the term “default” to describe the men’s clothing; rather she uses “unmarked,” which implies agency. This discussion highly reminded me of Maddie’s discussion of the default sex as female and the “default”/unmarked/un-added-onto version of clothing as male.

[6] Tannen, Deborah. “Marked Women.” Reading Critically, Writing Well. Ed. Axelrod, Rise B., Charles R. Cooper, Alison M. Warriner. pp. 232-237. <http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=JQQoe7giCbUC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=clothing+%22michelle+obama%22&ots=QVkNEr1stO&sig=GGql9uekcdIv8qz9bOHrv7YFa7M#PPA237,M1>. 05 Mar 2009.

Comments are closed.

Natasha, you’re made of amazing. I heart you muchly.

I like how you arranged clothing as technology. The diagram was especially informative. (Also, you are hella organized. It’s almost thesis-like in organization)

(I don’t know if we’re supposed to be commenting on others’ papers, but the title caught my eye and here I am… :P)

Baibh (and all others)—

Yes! Please! Comment on/talk back to one another’s papers! I don’t much like being the only one….

Natasha–

What’s exciting to me about this paper is not just how complex it is—working its way through three facets of the genderized technology that is fashion—but how HOPEFUL: as you trace the various ways in which we are marked by the clothing we wear, you also detect ways in which those markings can alter→ actually be altered by the decisions we ourselves make. (My other course this semester—The Story of Evolution and the Evolution of Stories—is all about this idea: the inevitability of change, and the role we can play in facilitating it.)

“Clothing is not inherently gendered,” you argue, and so its valence has-and-can change, over time. “We perform ourselves,” you say, and so use our clothing (along w/ other markers) to indicate both identity and affinity. (Still unanswered for me is why our use value to others, unlike that of our coffee mugs, is so dependent on such gender markers…do you think this is sociobiological, a continual playing out of the sexual dynamic?)

Calling attention to “agency” is essential to your argument (though my husband the lawyer is fond of pointing out that, in legal discourse, an “agent” is someone who acts, not for herself, but on behalf of another). But perhaps your most striking point is the notion that having an unmarked default makes it harder (for men) to choose the non-default-option—and the reverse: that being always marked encourages a diversity of clothing expression (among women): If the norm is to express oneself, then lacking a default encourages the sort of playfulness that can lead to their alteration. By gradually altering how we mark ourselves we change the system.

I’d be curious to know, btw, what you make of the clothing my mother and sister discovered, while we were traveling in New Mexico together this week: What role does “women as art objects” play in your design?