“They touch with their eyes:” Scopophilia and visual representation in Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale

Michelle Bennett

3/29/09

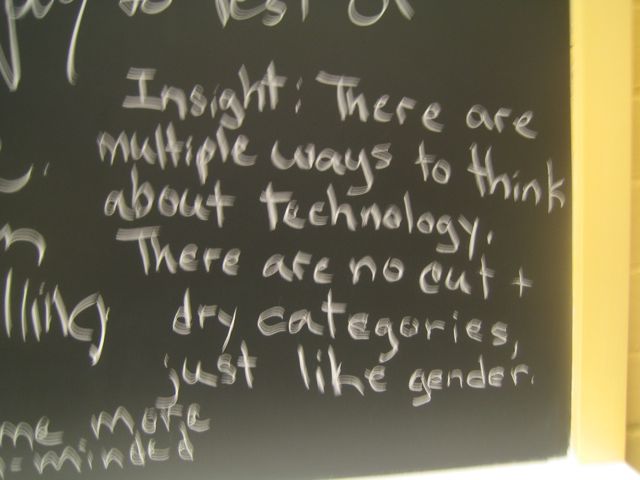

Gender and Technology

In her text, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Laura Mulvey identifies certain patterns in narrative cinema regarding the model of power between the gaze and the subject of the gaze. Among her many conclusions, she states that women in film are treated not as separate entities from the male characters, but instead serve only as reflective surfaces for the male characters, echoing their desires and motivations. This principle, in part, constitutes pleasure in looking at these female characters; on one level as erotic object, and on another level as an image of likeness. In Gilead, the fictive world imagined by Margaret Atwood in her novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, the lawmakers have attempted to thwart this scopophilia between men and women through various methods of control, such as the enforcement of an obscuring uniform or the vigorous policing and elimination of such media as magazines and films. These efforts, making the gaze more surreptitious and alluring, sometimes have the opposite effect of their intention, by making the desired object of the gaze more accessible, or reversing the order of power between men and women. The regard for spectacle and spectatorship in Gilead brings to light issues of gender discussed by Laura Mulvey and distorts to some degree the use and effect of visual or filmic representation previously established in Mulvey’s text.

Towards the very beginning of Offred’s transformation to handmaid-hood, we may detect a discussion between Aunt Lydia and the other “girls” that gestures towards some of Mulvey’s principles. In her text, Mulvey states, “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly” (62). In a moment in the narrative where tourists ask to take pictures of Ofglen and Offred, Offred evokes the memory of one of Aunt Lydia’s lecture to the handmaids in training, in which she articulates the unpleasantness associated with such a relationship that frames the male gaze as something confining and unjust: “I also knew better than to say yes. Modesty is invisibility, said Aunt Lydia. Never forget it. To be seen—to be seen—is to be—her voice trembled—penetrated. What you must be, girls, is impenetrable. She called us girls” (28). If we are to apply some of Mulvey’s principles to this scenario of tourism, the gaze is reframed as something that is foreign, curious, and intrusive. By considering Aunt Lydia’s use of the word, “penetrated,” this comparison also suggests that the act of looking turns into a sexual act, and an act that is perhaps not consented or reciprocated.

Because the residents of Gilead are made to fear and detest the unreciprocated and sexualized gaze, many media objects, such as films and magazines, have been removed. Mulvey acknowledges the sexualized nature of some of these media objects: “Woman displayed as sexual object is the leit-motif of erotic spectacle: from pin-ups to strip-tease…she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire” (62). Although there is largely an absence of these media objects in the narrative, there are still scenes in which the sexualized gaze intrudes on the pious scenes of Gilead. For example, when Offred and Ofglen walk back to their houses from the market, Offred sees the possibility of tempting the guards with the movements of her body:

…I know they’re watching, these two men who aren’t yet permitted to touch women. They touch their eyes instead and I move my hips a little…It’s like thumbing your nose from behind a fence or teasing a dog with a bone held out of reach…I enjoy the power…They will suffer, later…They have no outlets now except themselves, and that’s a sacrilege. There are no more magazines, no more films, no more substitutes. (22)

We may see the smallest hint of an upturning of the hierarchy of power in this passage. Because there is no “substitute,” no “outlet,” for the erotic charge that the spectators experience upon looking at Offred, she has the power to make them suffer by first, feeling pleasure in watching the movements of her body, and second, having to contain this pleasure within them. The lack of media objects in this case both brings the spectator and object closer together and reverses the schema of power between male gaze and female erotic object.

The reader sees this trend or power upheaval continue in the women’s regard for the commander. The women of the household anxiously await his arrival, and upon beginning his sermon, they watch his every move, while he reads the bible, and subsequently is unable to return their collective gaze. Offred comments on the strangeness of this role reversal: “To be a man, watched by women. It must be entirely strange…To achieve vision in this way, this journey into a darkness that is composed of women, a woman, who can see in darkness while he himself strains blindly forward” (87-88). It is clear in Offred’s paradigm of darkness and vision that the woman is now the active viewer and the man is the passive object of the gaze. Although the commander has the most power than nearly any other character we’ve met, he is reframed in this passage as someone that is subject to the dissecting and inquisitive gazes of all of the women who occupy his house. In this passage, Offred has effectively reversed Mulvey’s established model of spectatorship and scopophilia.

Atwood’s treatment and manipulation of Mulvey’s model of scopophilia reaches its climax during the passage in which Offred is being trained to be a handmaid, and Aunt Lydia shows footage of a protest from the past as cautionary material for the “girls.” Offred recognizes her mother in the crowd of protesters: “Now my mother is moving forward, she’s smiling, laughing, they all move forward, and now they’re raising their fists in the air. The camera moves to the sky, where hundreds of balloons rise, trailing their strings…” (120). By juxtaposing the images Offred is presumably shown onscreen with the image of Offred and her fellow “girls” being trained in the Red Center, the contrast is striking: the scenes of the footage become objects of fierce desire, as they hearken back to a time of relative freedom and happiness. Even the movement of the camera, “to the sky, where hundreds of balloons rise,” is indicative of freedom, while the lifestyle of the women in Offred’s world connotes routine and stasis.

Presuming that these women are being detained in the Red Center against their will, they become the subjects of the gaze, and the women onscreen, captured on footage at their most outspoken and active state, become the objects of desire. Both sides of the gaze are female, however, and this does not coincide with Mulvey’s model. However, at this moment, Offred literally experiences the pleasurable moment of recognition and likeness that Mulvey describes: “Here, curiosity and the wish to look intermingle with a fascination with likeness and recognition: the human face, the human body, the relationship between the human form and its surroundings, the visible presence of the person in the world” (60). Because this passage both gestures towards and upturns Mulvey’s model of spectatorship, by placing women on both sides of the gaze and also by inserting some form of recognition or likeness into the gaze, it is a paradox. It acknowledges the legitimacy of Mulvey’s claims, but also manipulates these claims for the purpose of providing the viewer with a disorienting view of Gilead and its comparative (dis)order. By manipulating Mulvey’s theories of spectatorship and scopophilia, Atwood effectively uses media objects, or the lack thereof, as well as other modes of spectatorship and desire within her narrative as tools to dissect and tinker with the established order of power in looking between men and women. This use of Mulvey’s theory has a jarring effect, contributing to the disorientation and disbelief we readers experience when transported to Gilead through Atwood’s novel.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Random House, 1998.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Feminism and Film Theory. Ed.

Constance Penley. London: BFI/ Routledge, 1988. 57-68.

Comments are closed.

What I keep thinking about as I read this is that even though the gaze coming from the women usurps the usual power structure of women being gazed upon is that the women are still oppressed. In some ways, what you suggest is that even when the women have the power to control or use the gaze, they still lack power. It also makes me think about the film of the female protestors. In that scene, the protestors display the possibility of equality with men while the girls in the Red Center seem to desire that freedom and while they are the spectators not the looked upon, they cannot have that freedom. Equality is achieved by covering women, but it’s not really equality. So what occurs to me is that the possibility the protestors imagined may not be possible. Which is a disturbing thought.