The de-sexualization of Dr. Manhattan

Cat/Catherine Bloxsom

Date April 2, 2009

Professors Anne Dalke and Laura Blakenship

Gender and Technology

Paper #3

The character, Dr. Manhattan, in Alan Moore’s Watchmen is nude in the majority of the novel. The representation of a fictional character, compared with a Calvin Klein ad of Djimon Hounsou, demonstrates that there is a paradox between technology and sexuality. In other words, technology has transformed Dr. Manhattan into a de-sexualized creature, while Calvin Klein created a sexy advertisement using only a pair of underwear.

Before Jonathan Osterman changed into a “superhero,” he was a scientist and a human, who wore clothing. It is not until technology goes wrong that the scientist becomes a cyborg, who does not wear anything. It seems that by not wearing any costume (other than a robe at times), Moore is emphasizing Dr. Manhattan’s non-human aspects. Although we see, as readers, Dr. Manhattan as a classical bodied statue, we also notice his blue skin, his dark inset eyes and the circle on his forehead. His classical bodied form only highlights his differences from the other characters. Karl Kraus, an Austrian writer and journalist, wrote about how we perceive clothing and the body. Dr. Manhattan’s nakedness seems unnatural to the reader, because “we perceive a clothed state as the natural condition…” (Kraus 242). The paradox that Dr. Manhattan has a male human body but is no longer human is significant. When the accident occurs in the lab, Moore purposefully keeps Dr. Manhattan in a male body, rather than completely transforming him into a totally different organism. Through the character’s nakedness, the author makes him stand out more than through his blue skin alone. Moore’s illustrations of a blue cyborg, depict Dr. Manhattan, as a de-sexualized character. Body language seems to be the key element in creating a sensuous body.

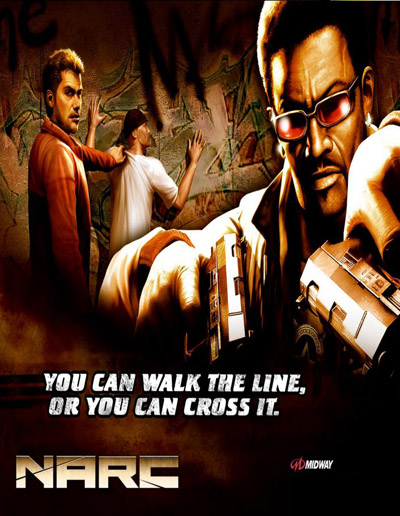

When juxtaposing a frame of Dr. Manhattan with a Calvin Klein advertisement of Djimon Hounsou, an actor and model, one can see how the positioning of the body changes the tone. The Calvin Klein advertisement eludes sex, while the frame of the Watchmen character communicates power and fear. Dijimon Hounsou is leaning back, standing relaxed with his hands above his head. His left leg is bent and placed behind the other, highlighting the curves of his body. Dr. Manhattan’s body, on the other hand, has a sharp, stiff structure to it. Although the Calvin Klein ad’s subject is real compared with Moore’s character, both are fictional in their representation. The model is posed in a black and white photograph, creating a sexy-feel to the advertisement.

Perhaps, the erotic nature that is in most Calvin Klein ads lies in not showing everything. The garment leaves little to the imagination, but it also brings attention to the rest of his body. The eroticization of the ad alone emanates from his pose, which is more relaxed than the machine-like images of Dr. Manhattan. Also, clothing can accentuate the contours of the body, producing a sensuous scene. Karl Kraus’ article titled “The Eroticism of Clothes” discusses clothing as a fetish. He states:

The excitement of exposure consists in the isolated display of a body part against the clothed surrounding area. Whereas the harmony of the completely naked body forces the eye to the synthetic comprehension of an organism, a bared body part draws the gaze hypnotically to itself and becomes the representative of an erotic idea, a fetish…Just as the sense of bodily shame experiences exposure more strongly than complete nakedness, so too is direct erotic sensation far more intensely aroused by exposure than by nakedness (242).

Kraus would say that the shape of the covered body in the Calvin Klein ad represents an erotic “idea, a fetish,” since it draws the eye to the exposed body. I would argue that it is not only the “isolated display of a body part,” or in this case the isolated display of one part of the body that makes the ad sexual. It is also the model’s body language.

Dr. Manhattan is drawn as a stiff, machine-like figure, so that his image can communicate his powerful nature. Through Moore’s representation, he is implying that technology has made Dr. Manhattan undesirable. Because of his non-human attributes the character’s nakedness is not sensual. The powerful, blue organism’s naked body is his only link to male gender and humanity. The Calvin Klein ad does not emanate this same power, although it does catch a passerby’s eye. The advertisement was made to be noticed, while Dr. Manhattan was made to show that technology is male. For example, Laurie, one of the only female characters, is a human superhero with no special powers.

She seems to desire the power that Dr. Manhattan possesses, which could explain her attraction. Her costume embodies Kraus’ idea about the body’s exposure, becoming “the representative of an erotic idea.” Her tight yellow dress alludes to the body, while covering it. Her poses and body language parallel the Calvin Klein model at times. Moore seems to be demonstrating that Dr. Manhattan is a synthesis of the male body and technology; while by comparison, Laurie is only a female and a human.

Through clothing and body language, the body can viewed as erotic. The de-sexualized representation of Dr. Manhattan reveals that his nakedness is unnatural. Laurie and the Calvin Klein advertisement, on the other hand, are viewed as sexy. The paradox that being covered is more alluring than being completely exposed shows how technology can make bodies more sensuous. Thus, in this instance, technology created one de-sexualized male superhero and one sexy advertisement.

Bibliography: Kraus, Karl. “The Eroticism of Clothes.” In The Rise of Fashion, edited

by Daniel L. Purdy, 239-44. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Comments are closed.

Reading through the various “third quarter” reports, I see that many of your classmates have called attention to how dystopic our most recent representations of gender and technology have been. In that context, it’s particularly refreshing (and useful) to have you demonstrate two different technological “results,” one sexualizing a model, another de-sexualizing a super-hero.

You have two points to make here. The first is that the curved body (vs. the machine-like qualities of the stiff one) is sensuous; the second is that the partially-covered body (vs. the unsexiness of the naked one) is alluring. (In Ways of Seeing, John Berger develops an interesting contrast between “naked” and “nude”–the latter inviting the sexual gaze–that might also add to your argument.)

But in neither case do you really emphasize the different technologies of representation @ work: what’s the difference (for instance) between a comic book and an advertisement, between a drawing and a photograph, between a colored image and a black-and-white one?

I did appreciate your incorporating images into your text–and would have liked to see an image of Laurie, too, as support of your argument that her tight yellow dress is “the representative of an erotic idea.”

I’m also a little confused by your beginning and ending w/ what you call “a paradox between technology and sexuality.” I don’t see the paradox. That technology can have different effects? What’s paradoxical about that? Or that we desire what we cannot see? But don’t we always desire what we cannot have? Isn’t that, functionally, the definition of desire?