Women in Cinematic Dystopias

It is simply impossible to write a 3 page paper on the top 50 dystopian movies over the past century, hence I chose to restrict myself to the visions directors Fritz Lang and Kurt Wimmer chose to envelop us in, partly because the societal structure and the contemporary dilemmas existing within these two plot synopses are distinct and similar in a lot of ways. The dystopian state of Libria in Wimmer’s ‘Equilibrium’ consisted of taking several hits of a drug called Prozium throughout the day in order to rid the human body of emotion which was seen to be the cause of all things, hated and destructive. When a high ranked official, John Preston goes against the mismanaged Tetragrammaton Council, this undesirable system crumbled as the film ended with a riot, indicating the fall of the Librian government. In Lang’s 1927 masterpiece, ‘Metropolis,’ a social divide existed between the workers and the capitalist who went by the name, Joh Fredersen. Rather than going into the elaborate details of this epic film which revolutionized the use of technology and sexuality within films today, it is safe to say that the outcome was similar to that of ‘Equilibrium’s,’ except for the ending montage where the capitalist was not overthrown, rather some level of harmony was reached between the two classes. This film could also be viewed as a Marxist representation of how capitalism can collapse.

Both the totalitarian nations which these films chose to incorporate reek of dystopian qualities. The social classes are strictly defined, freedom of thought is prohibited and eventually a hero does come along to bring about the change that the oppressed population has been waiting so long for. And of course, the omnipresent ruler has to exist, Joh Fredersen in the city of Metropolis and the ‘Father’ within Libria in ‘Equilibrium.’ Due to the innovations in special effects and technology that took place over the time frame difference between the two films, the living conditions of the Librians were remarkably well-off than the disadvantaged laborers toiling away 10 hours of the day. Another marked difference is how Preston, along with the Resistance members successfully destroy the suppressed societal framework, whereas Fredersen’s son, Freder only acts as the fake ‘Mediator’ (the ‘heart’ between the ‘head’ and ‘hand’).There was no indication whether things would get better for the menial workers; the camera does not offer the viewer the privilege to know the workers’ fates.

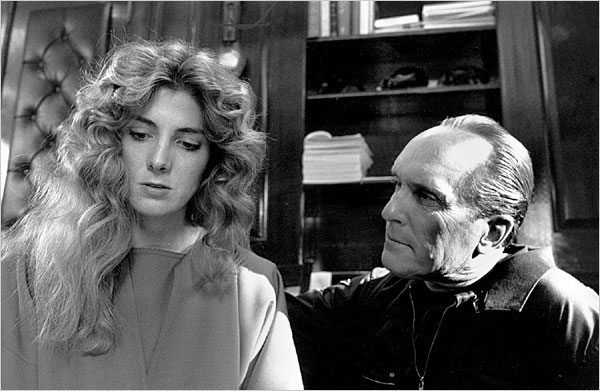

The main area of focus in ‘Metropolis’ appears to be on Rotwang’s creation of the ‘Machine-Man’ whose facial and bodily features took on Maria’s shape, the same angelic Maria who fluttered Freder’s heart and also instilled peaceful means of resolutions to the workers’ sorrows. The enigma arose as to why this demonic robot took on the bodily features of a woman since men dominated the technological world, especially during the Weimar Republic era. The only plausible reason could be that men want to control any form of ‘otherness,’ in the hopes of controlling nature itself. Maria was seen as a ray of hope for the underground workers, something which Fredersen could not stand since it undermined his competence in running his divided empire. Joining forces with Rotwang might have created the ultimate super robot which could control the masses of men, both upper and lower class, but the robot did spin out of Rotwang’s control. So women, whether they are programmed or human, cannot be controlled. Although Maria was not the ‘Mediator’ of the film, she was the in initiator of this uprising which did add some remedy to the harsh times the workers had to face. A very similar feminine character was present in ‘Equilibrium,’ but her role in Libria’s fascist environment was less profound. Mary, her name was. She stopped taking her daily dosages of Prozium and became a sense-offender. Unrequited passion erupted between her and Preston; she was sentenced to death while Preston went off to save his fellowmen. Prozium can be seen as the pharmaceutical technology restricting any form of nurturance from the women in Libria and Mary’s utter refusal to digest this drug is another form of feminine resistance. Both these films portray women as the fuel behind the fire in transforming the dystopia into a closer version of utopia.

Although both the films center on the destructive potential technology represents, it is necessary to view the minimal important role the women have to play within the films’ oppressed societies. The male gaze of Maria, when she becomes the machine and does her exotic dance, is one of the most important scenes, since the men become fascinated by her antics. The very invention man attempted to control ended up controlling him. ‘Equilibrium’ had no such female robots dance vulgarly, but the quiet demeanor and resilient faith that Mary possessed was enough to convince Preston about the shortcomings of the warped reality he lived in. The focus of most dystopian films (other examples include V for Vendetta, Minority Report) tend to be on the male protagonist’s heroic attempts to rid the world of all evil, but the source of the hero’s drive surprisingly stems from the woman’s pain/persuasion.

The climaxes of both these films also require some analyses. While ‘Equilibrium’ ended with the city of Libria plummeting into war, ‘Metropolis’ had a less violent vibe about it as some conflicts were sort of resolved by Grot and Fredersen shaking hands. So what messages do these films want to give to audiences regarding the attainment of peace and class equality? If inequality and tyranny is an ongoing feature of a society, what forms of improvements can a not-so-well-off person attempt to bring? If one has the means to fend for oneself, then aggressive tactics may not be necessary. Preston might have been an upper class wealthy cleric, but he had to resort to martial combat to bring down Libria. ‘Metropolis,’ on the other hand, contained Freder who possessed a lot of feminine qualities about him, something which might have been passed on from his deceased mother, Hel. The conclusions of these films might have been vastly different, yet they have ponderous aspects about them in terms of how dystopias should be dealt with.

Works Cited:

1. Metropolis (1927) by Fritz Lang. [DVD]

2. Equilibrium (2002) by Kurt Wimmer [DVD]

3. ‘Fritz Lang’s METROPOLIS and the United States’ by Michael Minden [Abstract]

4. ‘The Vamp and the Machine: Technology and Sexuality in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis’ by Andreas Huyssen

http://www.jstor.org/stable/488052?&Search=yes&term=machine&term=vamp&list=hide&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dvamp%2Band%2Bthe%2Bmachine%26x%3D0%26y%3D0%26wc%3Don&item=3&ttl=202&returnArticleService=showArticle

Comments are closed.

You chose, out of the wide spectrum of dystopian films made over the past 100 years, to analyze two that offer a striking study of compare-and-contrast. It’s interesting to hear your review of the ways in which the films are similar–their revolts, for example, being motivated by women—and different—with one ending in harmony, another in violence.

But there are a number of spots where I’m confused about whether you are calling attention to likeness or difference; the paper begins (for example) by saying that the “outcomes of the films are similar,” but it ends by saying that the “conclusions of these films are vastly different.” Which is it?

I also end the paper not knowing what I am to do with all these complicated likenesses-and-differences. You tell me that the films’ conclusions “have ponderous aspects about how dystopias should be dealt with,” but I’m not sure what they are: the need to use force, if one isn’t feminine, like one’s mother? The willingness to be inspired by a woman, when one wants to bring about change? How can you turn your catalogue of details into an argument built out of them?