Eye Opening: Western Culture and the Popularity of Double Eyelid Surgery Among Asian Women

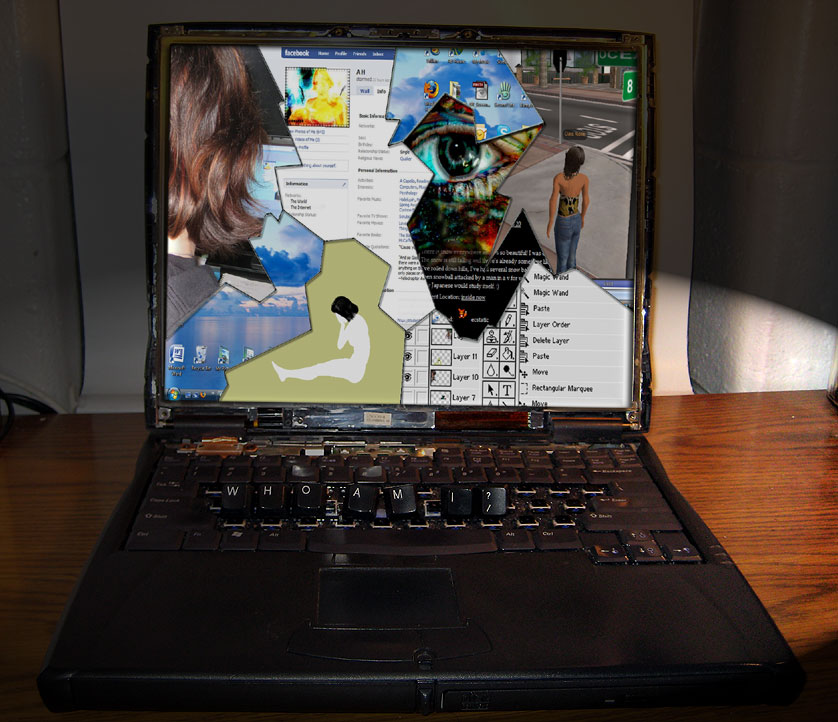

As a Filipina-American woman I feel torn between the need to fit into the culture of my adopted country and the responsibility to honor and respect my heritage. I was born in the Philippines but I grew up here in America. In a way I’m more American than I am Filipina. I speak with an American accent, I can understand my native language of Tagalog but I cannot speak it, and I love hamburgers. Yet there are always parts of me I prefer to keep essentially Filipina. Some of those features are my eyes. They are my grandmother’s with the almond shapes and the eye folds. Until I had watched an episode of the Oprah Winfrey Show about Asian women and their regards to beauty, it did not occur to me that some Asian women would pay to surgically construct eye folds when I had them naturally. The effect of this type of surgery called blepharoplasty (double eyelid surgery) gives the eye a wider, rounder look—a Westernized, Caucasian look. The cultural implications troubled me. Am I regarded as pretty solely because I naturally have eye folds? From that moment on I was convinced that double eyelid surgery among Asian women was one of several other ways for them to not only assimilate into Western culture but also to erase a part of their ethnic heritage as if this heritage was a shameful mark to bear. I have always believed that America was a country built and made up of immigrants. Even naturally born citizens (yes, even Native Americans), can attribute their heritage to other civilizations, no matter how many generations back, which originated in some other geographic location besides the Americas. So what does it mean to be American, to be westernized? What does it mean to be beautiful especially on the surface? Was there a standard for beauty regardless of race that took stock of Caucasian phenotypic traits as its basis?

Before reading the assigned articles I believed cosmetic surgery was for those with serious insecurities about appearance or for those who have serious health impediments such as a deviated septum that obstructs the nasal passage thereby, in some instances, makes breathing harder. Shows such as Extreme Makeover not only give the gift of confidence through beauty to people whom feel ugly but also attest to the growing popularity of elective surgery. But I never realized the ethnic motivations for such a surgery. Diana Dull and Candace West call attention to the ethnic/racial insecurities felt by many women and their need to be “normal”, meaning more Caucasian. The authors mentioned Jewish women who go into the offices of plastic surgeons requesting a reduction and narrowing of their distinctive Jewish noses. African Americans go into the offices asking for the same goals in rhinoplasty as well as lip reductions. Asians commonly go into those offices asking for eyelids. Now, I believe that all women should feel beautiful and if they feel that cosmetic surgery will let them attain their idea of beauty, then so be it. If cosmetic surgery will let them be the entire woman they can be, then so be it. My worry is that their standard of beauty, their standard of womanhood is based on Caucasian features. These women who want to alter their distinct noses, their full lips, and their no-fold eyelids are essentially erasing parts of themselves that makes them belong to their heritage. I believe they are not making themselves beautiful. Instead they are making themselves transracial and transethnic—from Jewish to Anglo-Saxon, from Black to White, and from Asian to Caucasian.

I know, I know. I may be a little too harsh in my judgments but the transracial and transethnic qualities of these surgeries force me to question the idea of what is normal. Victoria M. Bañales points out that “eyesight is not diminished nor restrained by eye/lid size” (137). Clearly Asian and Asian American women who undergo blepharoplasty do not partake in such surgery because of health reasons. The purpose of the surgery to make the eyes appear rounder and less slanted. In effect, make them look more Caucasian. Bañales also points out that eugenics, global capitalism, and the acceptance, nay, the adoration of Western trends has fueled this idea of white supremacy. To these Asian women, to be more White is to be more normal and more superior—a way to raise their social status. By these implications, they suggest that to be Asian, to have slanted almond eyes is to be entirely other and to be inferior. Much like the Peruvian women in Bañales’ essay who reasoned that their plastic surgeries will raise their socioeconomic statuses by securing better jobs for them, the Asian women in Eugenia Kaw’s essay reasoned that their double eyelid surgeries will help them in “getting a date, securing a mate, or getting a better job” (78). These women see their new eyes as a way of acquiring prestige. Kaw also points out that the Asian American women interviewed for her study are motivated by a gender ideology that holds the responsibility of women to be beautiful at its core. In other words, because they are women, their primary concern in life is to be beautiful and therefore “they must conform to certain standards of beauty” (79). Apparently, one of these standards includes looking more Caucasian. I was rather intrigued that the women featured in the study denied looking more Anglo as the reason for their surgeries. They instead stress that natural, phenotypical Asian eyes that are small and almond shaped give the appearance of lethargy since the person looks “sleepy”. In 1964, a Caucasian American military surgeon who performed blepharoplasties on Koreans during the American occupation noted in his journal that the “absence of the palpebral fold produces a passive expression which seems to epitomize the stoical and unemotional manner of the Oriental” (Kaw, 82). This notion of passive expression and stoicism attests to the racism that not only the doctor feels towards Asians but that Asians also feel towards themselves.

I, for one, am saddened by this assumption that Asian eyes are unpretty. In Westernized culture, is not individualism something to strive for? The idea of conformity, especially racial and ethnic conformity troubles me. This is simply Un-American. While these Asian women feel that blepharoplasty is just one way to fulfill not only the need to assimilate to Western culture but also to fulfill the responsibilities of their gender. To them, beauty equals gender. The woman’s ability to attract a man asserts her femininity. To me, blepharoplasty is one way to erase ethnic heritage and to betray oneself.

Additional References

Medicalization of Racial Features: Asian American Women and Cosmetic Surgery

Eugenia Kaw

Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 7, No. 1. (Mar., 1993), pp. 74-89.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0745-5194%28199303%292%3A7%3A1%3C74%3AMORFAA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-U

Comments are closed.

One of the most intriguing things about your paper is the way you bring up the conflict between America as a “nation of immigrants” and cosmetic surgeries that erase ethnic identity. You mention this, too, in terms of America’s ideal of individualism, which doesn’t seem to apply to physical appearance. Why is that? If you see these differences as beautiful, as expressing individuality and cultural heritage, why can’t they? And what relationship does this have to gender? Is this only true for women and not for men?

I’m also intrigued by your suggestion of internalized racism as one explanation for why these women don’t see themselves as beautiful with their “natural” features, and yet, the women often don’t overtly express this racism when they discuss their reasons for surgery. I wonder if they really do know that what they want is to “look more white” or if they have really rationalized this so much that they no longer believe that that’s the reason. Like we discussed in class, I wonder if suggesting to these women that they are erasing their heritage would make them change their minds or if that’s even desirable.