gandt in Digger and Digger v. Watchmen

Note: This may spoil the plots of both Watchmen and Digger.

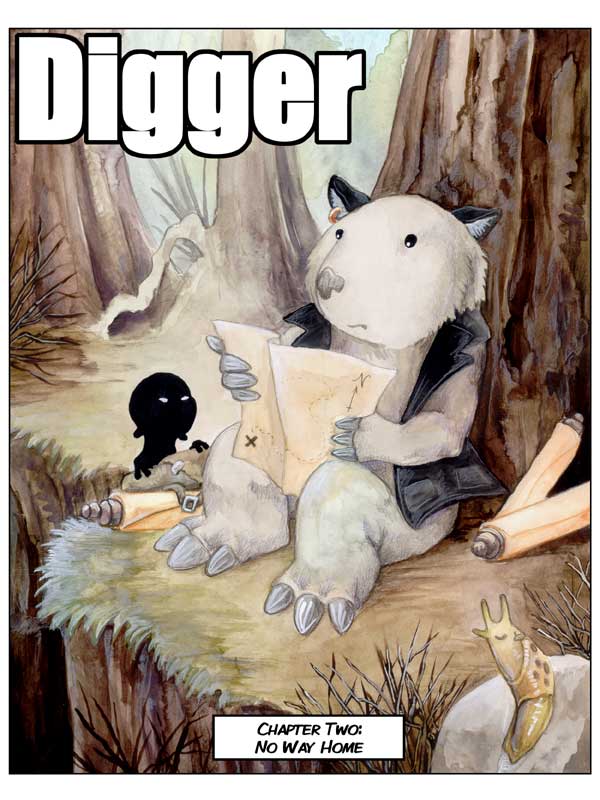

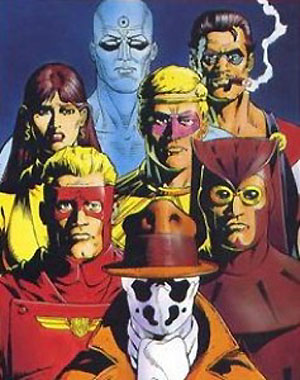

This paper is a short exploration of the contrasts between the webcomic Digger and the graphic novel Watchmen as well as an exploration of gender and technology in Digger. The webcomic – like a graphic novel in that its focus is not comical and has a plot – is about a wombat named Digger-of-unnecessarily-convoluted-tunnels, but usually called Digger (pictured above). While available in book form, my experience with Digger is solely through the internet. In reading Digger, I was intrigued by the many differences between it and Watchmen. The first difference I noticed was violence content. Digger, while having fight scenes, does not have very explicit violence the way that Watchmen does. This led me to my second thought, about expected reader. For Watchmen I though the reader was an older teenager or young adult, whereas for Digger, I thought either pre-teen or younger teenager. Perhaps this is for the more fantastical nature of the comic (it is set on a world similar to Earth, but the gods are much more present and magic exists and some animals talk …), whereas Watchmen is set on Earth in a relatively recent time period with human characters. I think a more important difference however is the gender roles that the two comics portray.

One reason the webcomic Digger interested me was the ambiguity of the main character’s gender. In fact, Digger’s gender is not named until the second chapter, on page 123, when a slug calls her sister. Not only is Digger’s gender rather ambiguous, so are many of the other characters, main and not-so-main. The comic even has humans, some immediately identifiable as male or (but not both) female; however, I estimate that about half of the humans are veiled and not obviously gender-able. This gender ambiguity is a striking contrast from Watchmen, in which every character (excluding the dogs) are immediately gender-able. The following hyena, a key character in Digger, is female (living in a female dominated society) as first shown in the comic:

This ambiguity’s connection to technology is in the form of genre or communication. By telling this story as a webcomic or graphic novel, the author was able to avoid gendered language and simply use the first or second person in internal or inter-person dialogue. This is because all of the action was depicted as pictures, so the author never had to say, ‘then she crawled down the tunnel’, the reader could simply see this. Again, this is in sharp contrast from the Watchmen where the picture is used to heighten the gender sense. Put another way, I think that in Watchmen, seeing pictures made me even more aware of each character’s gender than if the story had been solely text.

Perhaps this ambiguity of gender is simply a reflection of the bigger ambiuity of ‘right’ and ‘wrong.’ One character in Digger is called Shadowchild (possibly an orphaned baby demon, also pictured in the cover); Shadowchild asks Digger questions about morality. In doing this, the question is posed to the reader: “what is evil?”, “how do you know if something talks?”

The reason this last question is a moral question is because Digger told Shadowchild that no one should eat something that talks. Further, not only are the questions posed, they are never (at least as far as I can tell – the webcomic is not finished yet) completely answered. For the eating talking creatures question: They never determine a fail-proof way to determine if something talks:

In fact, Digger herself eats a piece of liver from a hyena (hyenas talk in this story) as part of a burial ceremony for it. Shadowchild is, of course, horrified to learn this. Another theme of this story is more existential – Shadowchild does not know what it is, they meet a human with a head of a deer and the first question Shadowchild asks it is: Are you a deer that talks? Perhaps more importantly than the asking of tricky questions, is the sense throughout the story that each individual needs to think about these questions and _choose_ the more appropriate thing to do and that this is what makes the world a nice place to live in.

Perhaps I am not reading enough into Watchmen, but the sense I got from Watchmen was more that the world is the way it is and it is terrible. I did not sense that the Watchmen was asking the reader moral questions of whether Jon should have killed Rorschach or whether Adrian should have killed millions of people. I am not really sure what Watchmen was doing, actually.

One question I do not see to be able to answer is exactly what role technology plays in moral ambiguity. Or perhaps I need to ask what role time plays in it. Digger, written in 20 years after Watchmen, has much looser take on gender. Is this an indication that Americans are taking a more loose view about gender roles and definition? What holds me back from this thought is that Watchmen just had a movie come out based on the graphic novel that did not attempt to bend any of the gender roles. Perhaps the internet allows less popular graphic novels to start existence and gain more of a foothold on the public’s attention than had the internet not existed. Giving more people access to public distribution of graphic novels may allow more fringe art to appear. Perhaps it is not the technology per se that enables this, but the access. This is a question I think needs more thought.

Works Cited

Gibbons, Dave, John Higgens and Alan Moore. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics, 1987.

Hiller, Jordan. Watchmen 2009. 12 March 2009. Bangitout.com. 3 April 2009. <http://www.bangitout.com/articles/viewarticle.php?a=2507>

Vernon, Ursula. Digger. 2 April 2009. WordPress with ComicPress. 3 April 2009. <http://www.diggercomic.com/>

Comments are closed.

Like you, I had lots of problems w/ Watchmen, and it sounds like for the same reasons: I was put off by the genderization and sexualization of the characters, more put off by the violence, even more put off by the amorality of the graphic novel. The book seemed pervaded with a sort of shallow nihilism that I found chilling—and finally, boring, because it didn’t offer any way “out.”

So I am of course delighted to see you use your efforts, in this project, to highlight a very different sort of text, one that is ambiguous—and so intriguing–in all the ways Watchmen is not: that uses the technology of visual presentation to play not only with gender ambiguity, but with moral ambiguity, that asks unanswerable questions, and so encourages a child to go on thinking about them.

Your own text is also sort of “wandering” and ambiguous: it drifts from one observation to the next, generally and gently “pondering” various possibilities. (I’m grateful, btw, that that wandering includes so many images—thanks for including them as “data” in your study!)

I do think the question w/ which you end is perhaps the most interesting one you raise: what role might various new technologies—such as the ability to distribute graphic novels free as webcomics—play in our exploration of moral questions and pursuit of moral answers? One answer might well be the one you offer—that of increased access, and increased play in the “fringes” of new possibility. But there are other less cheerful possibilites as well, such as the one Andy Clark considers in Natural-Born Cyborg:

… a new danger that accompanies the creation of more and more specific … electronic communities….the danger of a new kind of marginalization. By relying upon an electronic community in which it is easy to speak of unusual needs and passions, people with special interests may find it easier to live out the rest of their lives without revealing or admitting this aspect of their identity. This could be dangerous insofar as it artificially relieves the wider society of its usual obligations of understanding and support, creating a new kind of ghetto….