Femininity and Spectacle: from Metropolis to RuPaul

From the singular image of a painting, to throwaway images found in newspapers and magazines, it’s impossible to spend a day in the United States without encountering media images. These media images are entirely dependent on technologies to be produced and circulated, but also dependent on cultural forces to be created and consumed. The relationship of this technology, or any technology, to the larger society it exists in is complex. On the one hand, technology is a product of culture, created and controlled by individuals and audiences. It reflects and reacts to the culture which produces it. But at the same time, technological innovations change what is possible in society. The female body has been a subject of representation for centuries, and has a particularly complex relationship to the technologies used to represent it.

Attitudes toward the female body have changed dramatically since the evolution of media technologies of representation. In The Beauty Myth, for example, Naomi Wolf discusses the preoccupation with the shape of the female body as a replacement of a public interest in women’s virginity, a shift which occurred alongside changes in technology. Another theorist/critic, Laura Mulvey writes about representations of the female in film and photography, which are wholly dependent on technologies. Mulvey discusses the implications of a male-gendered camera being used to represent femininity, and the ways in which it is possible to make a truly feminist film, if at all. However, the question still remains if filmic and photographic technologies instituted a particular attitude toward women, or if those technologies exist as they do because they were shaped by attitudes toward women which already existed.

While representations of the female body are crafted by individuals for the consumption of society, technology has fundamentally altered our relationship to the female body. Media technologies are what have allowed the female body to be made into spectacle, and then circulated freely throughout the United States and the world. The intersection of a subject’s physical body with spectacle has profound implications for societal and individual experiences of the body, both for a relationship with one’s own body and perceptions of the bodies of other individuals.

Representations of the female body are nothing new. What has changed on a societal level, though, is the prevalence of images. Before photography, newspapers and magazines became so widespread, images were reserved for elite classes. Objectifying women through images, too, is nothing new, and is not a practice reserved for new media. Orientalist painting practices came with the imperial drive from Europe into Asia, and artists depicted all parts of Asian society as exotic and “other.” Women were represented naked or partially-naked, often as a part of a harem fantasy; it was more culturally acceptable to depict non-Western women in this hypersexualized way, the echoes of which can still be perceived today.

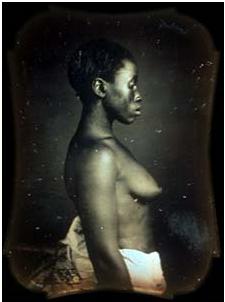

Odalisque with a Slave, Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, oil on canvas, 1839-1840 from www.orientalism.us

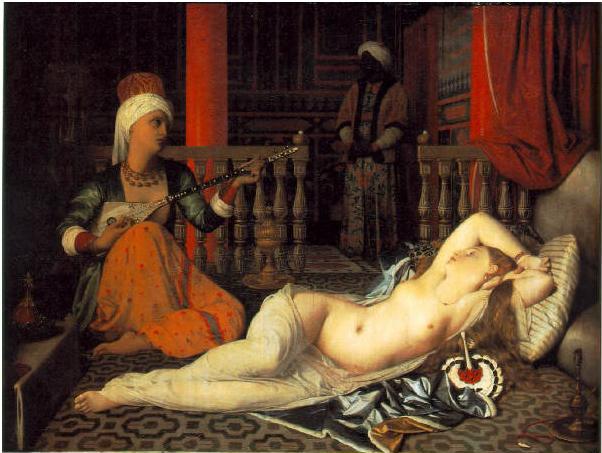

One of the most disturbing examples of objectification I have come across are the Louis Agassiz slave daguerreotypes. In 1850, scientist Louis Agassiz commissioned a photographer to take daguerreotypes of slaves in an effort to prove that the different races originated in different species. He treats the subjects as specimens and objects of study, and shows the dangers and traps of visual representations. The only knowledge the viewer can have of these individuals is their physical body, which has been shaped by hard labor and posed by a photographer. There was an intention to access some truth about these subjects through the photographs, but as contemporary viewers we can see Agassiz’s agenda has a huge influence on how we experience these images.

The OED defines a spectacle as “a person or thing exhibited to, or set before, the public gaze as an object either (a) of curiosity or contempt, or (b) of marvel or admiration” and “a thing seen or capable of being seen; something presented to the view, esp. of a striking or unusual character; a sight.” In class, we discussed the representations of Maria and the robot version of Maria in Metropolis. This film is a particularly useful one to examine, since it is such an early film, and one of the first to use spectacle in its depiction of the female form:

In the case of Metropolis, this sequence does little to advance the course of the narrative. It is a moment of visual indulgence, in which the audience is forced to engage the image of the body of robot Maria. The heavy reliance on the visual privileges the bodily aspect of the female subject; with only knowledge of the visual, in this moment the audience does not have access to any other part of the woman/robot represented.

The spectacle of this scene does not lead to deeper understanding of character or motivation of robot Maria, but instead calls attention to the subjectivity of the men looking at her. Their gaze is highlighted in the shots showing them looking at her, and the viewer is aware of their lust. At the same time, the shots of Freder having this vision reveal his anxiety and concern; later, we know he is motivated by his feelings for Maria and his need to stop this robot version. Throughout the film, the implied perspective is Freder’s, and in this case we alternately view the female body as a male spectator or as Freder, a male spectator with moral rather than sexual motivations for “looking.” In this way, as much as the audience is watching Maria, the sequence is more about the experience of watching her than it is about her. The audience is made more aware of their own spectatorship, their position of watching the film, because the act of watching is reflected within the space of the film.

The implications of being represented through spectacle for a fictional character, who exists only within the mechanics of the film, suggest that this character is purely sexual, or at the very least has little interiority behind her physical appearance. There is, however, a real woman behind this representation, and even though the gaze of the camera is assumed to be male, there are real female consumers of this material. So what happens when a woman, who is not intended to be a fictional construction, is represented in this way?

To answer this question, Laura pointed me toward the Janet Jackson Superbowl scandal. In 2004, during the halftime show at the Super Bowl, Justin Timberlake ripped off a piece of Janet Jackson’s costume, exposing her breast on live, national television. If you missed it, here’s the video:

The Super Bowl halftime show has always been one of the most spectacular events of the year in the U.S. In most football games, halftime is also the time to showcase cheerleaders, in effect making a sexual spectacle of the female body. The event, and the reaction to the event, say a lot about our society’s understanding of the female body.

There are several similarities between this clip and the Metropolis sequence already discussed. The technology involved – the camera – is recording a performance, though the goal of Jackson and Timberlake’s performance is not to take control of the spectator, as the robot Maria attempted to control her male audience. The role of the audience as spectator is not in question; viewers expect to be stunned by a visual event, and so there is no attempt to hide the technology involved in representation. The stated and understood goal is to create a visual, spectacular experience, as opposed to classical Hollywood film, which attempts to create a narrative so seamless that the viewer is unaware of the limits of the frame. In this clip, too, the audience is not just shown the events onstage; there is also footage of an excited audience watching Timberlake and Jackson onstage, and even watching the camera film them. As in Metropolis, watching others in the act of looking makes the viewer more aware of their own spectator position. Jackson and Timberlake are both portrayed very sexually, singing suggestive lyrics, and grinding onstage, just as the robot version of Maria was in a very sexual position. A key difference, and I think a noticeable difference, is that until the very end of the sequence, Jackson is heavily clothed. Her outfit calls attention to her legs and breasts, but does not show much skin, which is unusual for a female pop singer. Infamously, though, it did not stay this way. Timberlake rips off part of her shirt, leaving her breast and nipple momentarily exposed, at the same time singing “I’m gonna have you naked by the end of this song.”

It’s impossible to talk about this scandal without the media, public and federal reaction. In another similarity to Metropolis, a comment on the YouTube video reads: “BOOB!!! (Janet Jackson’s boob in public is a sign of the apocalypse. The end is near!)” The commenter is, of course, mocking the extreme media reaction to the exposed breast. Robot Maria’s sexuality, however, is also depicted as a part of the apocalypse, paired with text from Revelations and images of Death walking out of a church. This comment points to the fact that we cannot escape thinking of the female body and female sexuality as being “the end of the world.”

An article in the New York Times describes the event as the “game’s most spectacular fumble,” and suggests that there were signs it was not accidental, though MTV later issued an apology. A CNN article describes the reaction of the FCC chairman, who proceeded to launch an investigation of the entire half-time show, and the call to fine all stations remotely connected to the halftime show.

Certainly, Jackson’s breast was exposed in the context of a very sexual song, and many parents and watch groups were right to be concerned that they could not control their children’s access to sexual material, which was not expected in the halftime show. However, there was no consideration made of other possible “readings” of a breast, connected to non-sexual femininity and breastfeeding. The female body, in the context of a spectacle such as this one, can apparently be interpreted no other way than sexually. Also, though there clearly must be more the Janet Jackson than her body, it is the physicality of herself as a subject that is privileged in this spectacle, as happens with cheerleaders, other pop stars, models and other visually sumptuous representations of women.

I think it’s clear that these representations of women in the media come require a culture which produces, supports and consumes this kind of spectacle. If we were not drawn to these images so strongly, they would not exist. However, their existence, and extreme rate of circulation, depends on technology. The production and circulation of spectacular images of female sexuality creates an aesthetic, which others then reproduce; it is not one or the other that creates this phenomenon, but both cultural and technological forces working together. Mass culture, as it exists today, could not exist without the technology to produce it on a mass level.

It’s easy to see the effect of privileging the visual, sexual parts of the female body over other aspects of feminine subjectivity. A recent article from the Associated Press, “Worry over weight: Poll finds health disconnect” describes the effect of overvaluing the visual on psychological and physical health. It quotes Dr. Molly Poag, chief of psychiatry at New York’s Lennox Hill Hospital, who “points to women athletes as much better role models than supermodels: ‘There’s an undervaluing of physical fitness and an overvaluing of absolute weight and appearance for women in our culture.’” This quotation can be read in terms of visual culture: it is better to value the actual state of fitness to achieve thinness, rather than the appearance of thinness which models present. Later, the article quotes the head of the women’s heart program at the New York University Langone Medical Centry: “People can’t see the damage that’s being done inside their body… If you increase your fitness but don’t lose as much weight, you still have a lower heart disease risk than someone who is obese and sedentary.” Again, the physical appearance of fitness presented by weight is not as important as the actual act of exercising.

Many of us have struggled with body image issues, and there is a reason it is called body image. People, especially but not only women, tend to become preoccupied with physical appearance, whether it’s a matter of weight, skin, hair, etc. The scope is so narrow of what is presented as visually appealing in terms of the spectacle of femininity that is circulated, that many can never achieve that ideal. And yet, in the visual media, the appearance is privileged over other qualities which cannot be represented visually. In addition to contributing to body image problems, these images leave very little room for variance in femininity. Those who are not cisgendered, and those who do not ascribe to the traditional cultural aspects of gender, have no place in this representation of sexuality. Historically, when individuals deviating from the gender binary were included in spectacle, it was in a sideshow context. “The bearded lady” is a cultural trope we still have trouble getting rid of.

More recently, drag is challenging the place of gender roles in spectacle, though these images have not been mass produced on a level that more traditional images of gender have. In a drag queen show, the biologically male performer enacts a female identity, which is wholly spectacular, fantastic and often ostentatious. RuPaul, pictured below, is one of the most famous drag artists.

The example of drag is important. It engages in the act of genderfucking, and engages the audience with a striking visual image, like the other examples of spectacle and femininity, but it draws our attention to the contingency of gender. Rather than locating the feminine in the sexualized, physical body, femininity is located in a set of behaviors, clothing and accessories that can also be performed by someone biologically male. There are also drag kings, and faux queens, who are biological women who perform in the exaggerated style of drag.

Drag, also, demonstrates how culture can influence technology. We are all active subjects, as much as we are situated within a specific society and culture which has already been established for us. Drag takes the same technology used to privilege the visual aspects of the feminine, such as film, photography and performativity more generally, and utilizes that same technology to critique culturally accepted notions of gender. Its over-the-top, visual emphasis is appropriate to play with issues of femininity, since we have seen how the visual and the spectacular are so crucial in constructing notions of femininity.

Spectacle, then, while it has been used to construct objectifying, flattening perceptions of identity, can also be used to call attention to the constructedness of femininity, and to critique the very notions it establishes. Other kinds of artists have been engaged in this kind of work. A prominent example is Cindy Sherman, who uses photography to construct fake film stills, always using herself as the subject, and dressing herself as different kinds of women. She places herself as both object of the gaze and controller of the camera, and by changing her identity in each image, also calls attention to how we understand the feminine. The question remains of how these theoretical challenges, established in drag and other art work, can move outside of an intellectual realm. Changing how individuals think and perceive the world is important work, but it must move beyond those who have been able to take a college level course about gender. With an understanding of how femininity is constructed, people can change their relationship to their own bodies, and it other people’s, for the better. Everyone must be an aware consumer of images, and perhaps images are the best place to start.