“We Will Sing the Love of Danger”: Italian Futurism and Imagined Representations of Gender and Technology

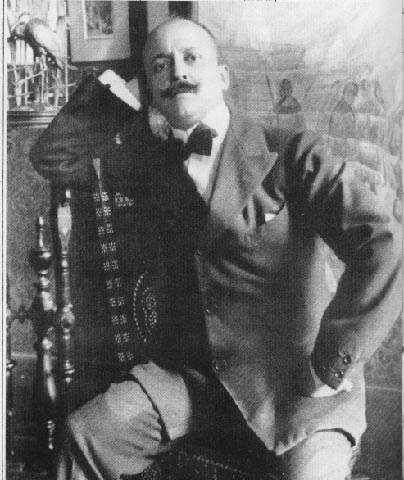

I am particularly fascinated by the aesthetic similarities between the design of Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” and the imagined world of the Italian Futurists, a group which have long simultaneously interested and repulsed me. The Futurists as a group were a closely connected batch of painters and theorists led by the poet Filippo T. Marinetti who wrote the Futurist Manifesto, published in 1909, which reads “We will sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and boldness …We will extol aggressive movement, feverish insomnia, the double-quick step, the somersault, the box on the ear, fisticuffs. We will declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty-the beauty of speed. A racing motor-car, its frame adorned with great pipes like snakes with explosive breath-a roaring motor-car that seems to run on shrapnel is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace” (Norden 108). And it only gets more rapturous from there.

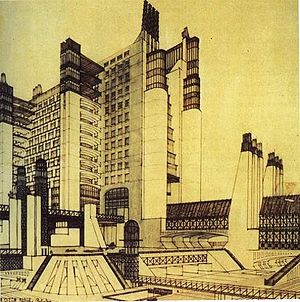

The futurists glorified violence, aggression, speed, and dynamism- all of which they saw as antithetical to the feminine. Deborah Johnson writes that Futurism was “not only implicitly hostile to women but programmatically misogynistic. The Futurists’ ideology of “contempt for women,” “struggle against feminism,” and “endorsement of violence and aggression as foremost values” is an extraordinary document of the backlash against women’s sociopolitical progress of the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries,” (Johnson 98). Their paintings strove to depict movement and militarism, and the urban design associated with the movement was conspicuously devoid of people, instead focusing on huge transportation hubs and automated factories. Futurism’s influence on many avant-garde films of the 1920s is well documented. In “The Avant-Garde Cinema of the 1920s: Connections to Futurism, Precisionism, and Suprematism,” Martin F. Norden describes how “Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’ (1927) is replete with machine motifs, from its opening montage of hyperkinetic machine parts to the creation of a female robot who leads the working class in a revolt. With these motifs and its portrayal of workers as machinelike automatons (they even move about mechanically), ‘Metropolis’ unmistakably bears the mark of Futurism” (Norden 109). “Metropolis,” while visually preoccupied with Futurism, is unequivocally a condemnation of the Futurist glorification of the automation of society.

Despite the fact that the Futurists claimed to despise and tear down all forms of tradition, their incredible misogyny represented a traditional view of the relationship between gender and technology and the role of women in society, a view which meshed quite easily with the militarism and pro-natalism of Italian Fascism in the 1930s and 40s. In her study of the relationship between Futurism and Fascism, Anne Bowler illustrates that for Marinetti “the originary moment of Futurism was critically related to the larger social and political crisis of Italy. From the beginning, Futurism found its ideal embodiment in the values of a nationalist campaign of war and destruction that was to inaugurate Italy’s rise to world power, the violent annihilation of the past, and a complete aestheticization of politics and everyday life” (Bowler 763-4). In the Futurist Manifesto, he wrote that war was “the world’s only hygiene,” (Bowler 763). This emphasis on the “aestheticization of politics” mirrors the Fascist program and allows for a consideration of the world of “The Handmaid’s Tale,” a world in which all previous forms of artistic and design expression have been streamlined into simple representation of function. Offred remarks that “they decided that even the names of shops were too much temptation for us. Now places are known by their signs alone” (Atwood 25). The all-seeing eye of the Guardians watches each citizen, and the Gileadean preoccupation with purity is a twinned obsession, emphasizing not only the purity of the body but the purity of the body politic.

Even the preoccupation with the sexual and reproductive lives of everyday citizens is a function both of Gilead and of Fascist Italy, in which the construction of the “sterile city,” (Horn 584) represented a threat to Mussolini’s economic and imperial ambitions. Government social scientists cast the urban environment as diseased. The government instituted various laws in the effort to increase the Italian population including a tax on bachelors “who, in the militarized language of the demographic campaign, were identified as “deserters of paternity,”” (584) mirroring the Gileadean construction of “gender treachery.” Further plans included a tax on infertile married couples, but were scrapped in favor of “positive measures,” including “cash prizes for marriages, births, and large families,” (585). Fascist social scientists believed that “the ‘virility’ of the Italian social body could be assured only through the fertile bodies of women,” (585) who were naturally characterized as incapable of any other social function. Futurist propaganda supported the pro-natalist agenda of the Fascists even while the Fascists constructed the Italian nation as generally anti-technological, and anti-urban in nature, ideas which directly contradicted the theoretical structure of Futurism.

The political deployment of imagined representations of gender and technology is also found in Watchmen, in which extreme jingoism and aggression is cast as masculine in character. The rejection of sentimentality, beauty, and the elevation of art to the platform of genius and antiquity significantly parallels the moral standpoints of the Comedian and Rorschach. Furthermore, the concept of the masked crusader, the superhero, in the context of Futurism corresponds most closely to the theories of women Futurist artists, specifically Maria Ginanni. These artists necessarily had to create alternate theories in order to survive within Futurism and retain a minimum of self esteem. Ginanni developed a conception of the Futurist Women which was characterized by “her desire for power, for the exceptional, and for the absolute…a refusal to acknowledge possession of a sexed and gendered body…This desire generates the image of a super woman who embraces the new possibilities offered by technology…and even aspires to dominate time and space. The impetus of this woman, however, tends to be curbed when she comes to terms with the world of men. At that point, she often becomes an imperfect man, or a matrix of virility,” (Sica 340). These Futurist women mirror quite clearly the desires of the women in “Watchmen,” who perform a desire for power, and in the younger Silk Spectre’s case, a desire to understand time and space as Dr. Manhattan does. However, they are stymied in their efforts. In this way, despite the Futurist woman’s “refusal to acknowledge possession of a sexed and gendered body,” the existence of the “world of men,” makes such a refusal impossible.

Futurism opens a door into the analysis of the relationships between theoretical conceptions of gender and technology and practical performances of such a relationship. Despite the claims that Futurism makes to the death of tradition, as in Gilead is actually predicated on the reproduction of tradition. And while Futurism represents a frame within which some women were able to build artistic and political lives, as the Watchmen had space for a very few women, it is not ultimately a space in which women and technology are allowed to easily coexist. Why, then, is Futurism is often only considered in the context of “art”? Why is it allowed to exist separate from its fascist and misogynistic connotations? Why does it hang on the walls of prestigious museums devoid of meaning and consequence, when the Futurists themselves were pledged to an ideology which proclaimed the destruction of art-for-art’s-sake and the very museum system by which it is now glorified?

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret Eleanor. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Anchor Books, 1998.

Bowler, Anne. “Politics as Art: Italian Futurism and Fascism.” Theory and Society 20 (1991): 763-794. JSTOR. Bryn Mawr College. 1 Apr. 2009 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/657603>.

Horn, David G. “Constructing the Sterile City: Pronatalism and Social Sciences in Interwar Italy.” American Ethnologist 18 (1991): 581-561. JSTOR. Bryn Mawr College. 1 Apr. 2009 http://www.jstor.org/stable/645595.

Johnson, Deborah. “Review: [Untitled]” Art Journal 57 (1998): 98-99. JSTOR. Bryn Mawr College. 1 Apr. 2009 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/777981>.

Moore, Alan. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics Inc., 1987.

Norden, Martin F. “The Avant-Garde Cinema of the 1920s: Connections to Futurism, Precisionism, and Suprematism.” Leonardo 17 (1984): 108-12. JSTOR. Bryn Mawr College. 1 Apr. 2009 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1574999.

Sica, Paola. “Maria Ginanni: Futurist Woman and Visual Writer.” Italica 79 (2002): 339-352. JSTOR. Bryn Mawr College. 1 Apr. 2009 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3656096>.

Comments are closed.

I like the way you tried to connect the three works together using the concept of Futurism, but I’m not sure it worked for me. I found myself losing track of the connections. This could be as simple as the fact that the first paragraph seemed to indicate that the whole paper would be about Metropolis. I think perhaps I just need some more markers about the relationship between the different works as well as of the works to Futurism.

That said, I think you have some really interesting ideas here. Futurism seems to want to rid the world of women or at least of femininity and yet, all these works seem to point to the need for femininity, except maybe The Watchmen. I like how you point out the devastating effect on the women in The Watchmen as well as in Futurism. They struggle to be included by denying their femininity, which pretty much erases their identity.

Metropolis seems to have a more complex relationship to the Futurists. The use of a female—and very feminine—robot to stir up the workers, is on the one hand, something the futurists might fear, but also applaud in its violence and aggression. On the other hand, the real Maria feminizes the mechanical nature of the world thus making it more bearable for everyone. I think there’s a lot to explore there and perhaps focusing on Metropolis would allow you to dig deeper into its relationship to Futurism.