The InterSEXion of Gender in Public Places

Baibh Cathba

“In Western culture, women have not long been full citizens, and in that respect it is no surprise that they have been historically excluded from public space. The world outside the home was once considered unsafe for the “fair” sex; women who did venture into that world without a male chaperone were thought to be of the worst kind, and asking for trouble. With the advent of the mall, women were for the first time allowed out of the house alone, but the rest of the public domain, including streets, restaurants, bars, coffee houses, and all other areas where anything exciting or political ever happens, remained in the hands of men.”[1] – Aiyana Berne

The stereotype of women is that they talk a lot, they travel in groups, want romantic relationships, and they shop at the mall a lot. But why should women congregate at a mall rather than a park? According to an article by Aiyana Berne, women are more at risk in public spaces outside of the house such as parks or bars, than in a safe indoor space like the home or a mall. Surprisingly, the quote from the article above was written in the early to mid nineties, when it was thought that the right to vote and the right to talk freely in public were finally available to both men and women. The argument of Berne is that even when women are supposedly safe in public spaces, there is an intrinsic fear that prevents their participation in public spaces which involves not only the male gaze but an overt sexual threat. In a time when women are supposedly free to join the workplace and entitled to just as much independence as men, there is still an underlying belief that one is less safe if they are walking alone. The idea that a woman is “asking for it” or bringing fault on herself for any sexual act of violence upon her person by violating certain rules is prevalent in the common rhetoric that defends rapists. In creating a fear of the public space, I believe there is a parallel to the exclusion of women from technological pursuits. How are women excluded from public spaces? They are excluded through the oblique use of sex and sexuality as deterrents to the participation of women in the public sphere.

The stereotype of women is that they talk a lot, they travel in groups, want romantic relationships, and they shop at the mall a lot. But why should women congregate at a mall rather than a park? According to an article by Aiyana Berne, women are more at risk in public spaces outside of the house such as parks or bars, than in a safe indoor space like the home or a mall. Surprisingly, the quote from the article above was written in the early to mid nineties, when it was thought that the right to vote and the right to talk freely in public were finally available to both men and women. The argument of Berne is that even when women are supposedly safe in public spaces, there is an intrinsic fear that prevents their participation in public spaces which involves not only the male gaze but an overt sexual threat. In a time when women are supposedly free to join the workplace and entitled to just as much independence as men, there is still an underlying belief that one is less safe if they are walking alone. The idea that a woman is “asking for it” or bringing fault on herself for any sexual act of violence upon her person by violating certain rules is prevalent in the common rhetoric that defends rapists. In creating a fear of the public space, I believe there is a parallel to the exclusion of women from technological pursuits. How are women excluded from public spaces? They are excluded through the oblique use of sex and sexuality as deterrents to the participation of women in the public sphere.

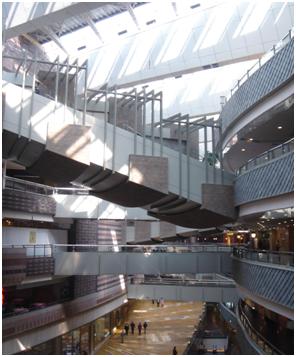

A public space, such as a park, is a construction.  There are thoughts and plans that go into a public space, there are budgets, there are measurements, there are aesthetics, and there are atmospheres. By creating a public space, it arguably becomes a technology. Even here on campus, we have examples of “women-friendly” steps by the gym formatted to the woman’s stride. In a joking manner, I’ve heard these steps referenced as the “rape steps” by people on campus, as the example of “woman-friendliness” most often given about these steps is it makes them easier to run since they are fitted to a woman’s steps. I believe that this reference as the “rape steps” is a short-hand way of referring to an anti rape tool for the women on campus. One company, Women’s Design Service[2], is dedicated towards making parks more “woman friendly”. The main things that they bring up concerning women’s utilization of public spaces such as parks are: height, strength, pregnancy, menstruation, breastfeeding, and longevity. While these things may appear unrelated to a park, the issues are related back to important aspects of the park. In a manner similar to the “rape steps” on our campus, the idea that women have a different stride than men is taken into account. By discussing strength, the company points out that the women who have to open gates to parks should not have to struggle with the opening of these aforementioned gates and latches and buttons on fountains should be at a reasonable and accessible height. This also applies to the idea of pregnant women and women who are breastfeeding. There should be areas in public in which such women have access to reasonable/adequate bathroom facilities and seating. The issue of longevity is addressed when referring to the idea of women living longer than men and needing parks to be accessible and friendly to those who are elderly.

There are thoughts and plans that go into a public space, there are budgets, there are measurements, there are aesthetics, and there are atmospheres. By creating a public space, it arguably becomes a technology. Even here on campus, we have examples of “women-friendly” steps by the gym formatted to the woman’s stride. In a joking manner, I’ve heard these steps referenced as the “rape steps” by people on campus, as the example of “woman-friendliness” most often given about these steps is it makes them easier to run since they are fitted to a woman’s steps. I believe that this reference as the “rape steps” is a short-hand way of referring to an anti rape tool for the women on campus. One company, Women’s Design Service[2], is dedicated towards making parks more “woman friendly”. The main things that they bring up concerning women’s utilization of public spaces such as parks are: height, strength, pregnancy, menstruation, breastfeeding, and longevity. While these things may appear unrelated to a park, the issues are related back to important aspects of the park. In a manner similar to the “rape steps” on our campus, the idea that women have a different stride than men is taken into account. By discussing strength, the company points out that the women who have to open gates to parks should not have to struggle with the opening of these aforementioned gates and latches and buttons on fountains should be at a reasonable and accessible height. This also applies to the idea of pregnant women and women who are breastfeeding. There should be areas in public in which such women have access to reasonable/adequate bathroom facilities and seating. The issue of longevity is addressed when referring to the idea of women living longer than men and needing parks to be accessible and friendly to those who are elderly.

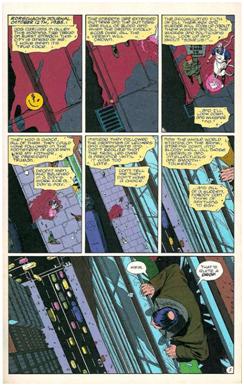

Another way of creating this public space is in graphic novels. The graphic novel gives the important sidestep to viewing familiar things in that the situation becomes a fantasy or a removed scenario which makes it easier to think about because it is not as immediate or in the reader’s face. One thing that The Watchmen gives to the reader is the idea that frank discussion of sex is necessary to finally understanding public spaces. The idea of public space is played with, as the reader is allowed into the lives of heroes and villains in the public and private spheres. The actions of the overly masculine superheroes are dissected at all times, giving a sense of public performance to the interactions of the characters. It allows the reader into intimate moments of thought, like when Nite Owl views himself as impotent unless displaying his vitality through the donning of his manly, high-tech superhero costume, as well as showing a more public vision such as the riots.

While the idea of a public space is not exactly evident in a graphic novel, the idea that something private as a book can give insight into the public lives of characters is valuable to understanding public space. In Watchmen, the concept of the public areas is especially important as the graphic novel does not focus on only one story; instead, the novel spreads the story over the city into the lives of many superheroes. The story is told in camera angles as well as public spaces. Considering that not many women are out in public spaces (with the exception of Laurie, a superhero, and the unnamed lesbian couple, who appear to be scrappy fighters), it is very much a “man city”, which emphasizes the masculinity of public spaces. Sally used to be out in public spaces, but is now confined to a nursing home (and even when she was out in public she had a protective male escort). Laurie never goes out in public spaces alone, instead she relies first upon Dr Manhattan, then upon Nite Owl to escort her about town. Most women are seen indoors, there is no unescorted crime fighting by women alone in public spaces. In all instances given by the graphic novel, the women are in a protective group. The one woman (The Silhouette) who does emerge into the public spaces unescorted is punished with death.

While the idea of a public space is not exactly evident in a graphic novel, the idea that something private as a book can give insight into the public lives of characters is valuable to understanding public space. In Watchmen, the concept of the public areas is especially important as the graphic novel does not focus on only one story; instead, the novel spreads the story over the city into the lives of many superheroes. The story is told in camera angles as well as public spaces. Considering that not many women are out in public spaces (with the exception of Laurie, a superhero, and the unnamed lesbian couple, who appear to be scrappy fighters), it is very much a “man city”, which emphasizes the masculinity of public spaces. Sally used to be out in public spaces, but is now confined to a nursing home (and even when she was out in public she had a protective male escort). Laurie never goes out in public spaces alone, instead she relies first upon Dr Manhattan, then upon Nite Owl to escort her about town. Most women are seen indoors, there is no unescorted crime fighting by women alone in public spaces. In all instances given by the graphic novel, the women are in a protective group. The one woman (The Silhouette) who does emerge into the public spaces unescorted is punished with death.

The public space allowed to women appears to be a space of exclusion; one might even go so far as to call public space a technology that is unavailable to women. Such underhand oppression in public spaces is subtly keeping women out of important roles and out of the public eye as role models. Will there be a solution to this fear of public spaces that will enable women to leave the house? Perhaps not until there is truly equality between men and women will it be possible to resolve the battle for public space.

Comments are closed.

This is a far-ranging paper (from malls, down the steps @ Bryn Mawr, to the graphic novel) that plays with that very old binary in gender studies, the notion of a contrast between “public men, private women.” I’m puzzled about how you get from one space to the next, and particularly puzzled by your treatment of the novel as a private place that gives insight into public lives (I would have described it as the reverse: a public space where interiority is showcased….)

There has actually been lots of work done recently on the re-engendering of public spaces. See, for example, Sarah Deutsch’s Women and the City: Gender, Power, and Space in Boston, 1870-1940; or—classically—Jane Jacobs’ work on The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which isn’t explicitly or only about gender, but argues that modernist urban planning neglects the “layered complexity and seeming chaos” of lived lives, and insists that the conventional separation of uses—into residential, industrial, commercial, for example—is a big mistake. We need childcare where we work, food where we live, etc….

On the other hand, researchers who study urban violence insist that the most dangerous spaces for women are their homes, where most damage is done by the people closest to them….