Women in Science

Hillary Cleveland

3/6/09

Rosalind Franklin and Nettie Maria Stevens have much in common. They were both women in science. They were both never married or had any children. They both died relatively young (37, and only 9 years after getting her Ph.D. respectively) from cancer. But they have something else in common; the men around them and doing research with them had a certain very similar opinion of them. They felt that these women were capable at doing experiments, but not as competent or capable of fully understanding the results. The men also classified them as timid in making decisions and judgments about their research. Because they died before their male counter parts, history has been left with this opinion of them. There has been a lot of work done to try and reclaim these women scientists and properly attribute the work they did to them, but there are still some opinions that have not changed. I think that there are plenty of reasons that these women are remembered the way they are. Some are societies’ fault, some are biology’s’ and some, though feminists would hate to hear me say it, are women’s fault.

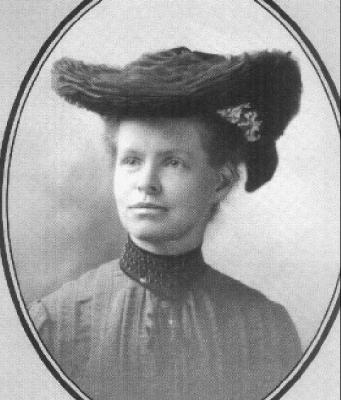

Nettie Maria Stevens was born in 1861 in Vermont. She went to a small college and was a teacher and librarian for a while before she decided to go back to school. She received her B.A. from Stanford in 1899 and her M.A. in 1900. Then she came to Bryn Mawr College and received her Ph.D. in 1903. After she received her Ph.D. she continued to do research at Bryn Mawr. She had been offered a position as a professor of Biology at Bryn Mawr, but she passed away before she could take it in 1912 of breast cancer. Her focus of research was in cytology and in particular working with the chromosomal theory of inheritance (particularly in reference to sex determination.

Rosalind Franklin was born in 1920 in Notting Hill, London. She went to Newnham College, Cambridge and passed her exams in 1941. Women in England could not get undergraduate degrees back then. In 1945 she received her Ph.D. from Cambridge. She worked on many things in her life. While still in England during WWII she worked on the structure of coal, after the war she went and worked in France. She really wanted to work in England however so when the opportunity arose she took it. She started working at Kings College in 1951. After the environment at Kings became too hostile and uncomfortable for her (due the controversies over the structure of DNA) she left and took a position at Birkbeck College in 1953. Her whole career was focused on discovering and understanding the structure of different things, such as the molecular structure of coal, the structure of DNA, and the structure of different viruses like the Tobacco Mosaic Virus. She passed away in 1958 from ovarian cancer.

These women greatly advanced our understanding of some of the most important things in biology, the discovery of the chromosomes that determine sex and the discovery of the structure of DNA and several viruses. There is no doubt that these women did not do the work on their own. Nettie Stevens was working at the same time and conversing with Edward B. Wilson as well as Thomas H. Morgan, the former and current (at the time of her research) heads of the Biology department at Bryn Mawr. James Watson and Francis Crick were also working on the structure of DNA at the same time as Franklin. They should not get all of the credit for these discoveries, but it is a great disservice to their name and all women in science and academia to think of them as incompetent or any less capable then their male counter parts. T.H. Morgan wrote and obituary of Nettie Stevens that belittled her importance in the lab and basically said that she was just a glorified lab technician. But earlier, before she passed away, he had described her as the most successful and capable graduate student he had had. Watson famously called Rosalind cold and unwilling to share her work as well as accusing her of being unable to interpret her own data and images, when in truth neither could he.

But what was the effect of these opinions of these women held by the men around them? They had obviously been found competent enough to get a Ph.D. and professorships, and yet they were characterized as being extremely cautious about making assumptions of their data. They were known for being absolutely meticulous about their work and sometimes were criticized for this. But why did they do this? I feel it was because they had to. The male scientists around them felt that these women who were in a traditionally male dominated field were not capable of dealing with the their (read male/masculine) technology (even though they were both known for their fabulous results that the men around them had never been able to achieve, Stevens had a microscope she altered to get a clearer image and Franklin altered the X-Ray crystallographer to take better pictures). I think that if these women had made snap conclusions about their work they would have been criticized for being impatient and incapable of deeper interpretation of their data. If they had been wrong they also would have been laughed out of the field. All of this criticism from men about women in academia has lead, I think, to women being more cautious about their work, preventing them from reaching their full potential. This case is evident for women in science because of societies’ gendering of technology, and science specifically, as a male dominated subject and thusly as masculine. Sadly these opinions are still around and women in science still face these criticisms today. Women in science need to prove themselves by careful research and presentation of their ideas, but they also need to take chances and help themselves breakout of this rut.

References:

Maddox, Brenda. Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA. HarperCollins. 2002

“Rosalind Franklin” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosalind_Franklin last edited 3/5/2009, visited 3/6/09

“Secret of Photo 51” http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/photo51/ , to view episode : http://www.youtube.com/view_play_list?p=BAF7F12F15C26151

Morgan, T.H. “The Scientific Work of Miss N.M. Stevens” Science, Vol. 36, No. 928, pg. 468-470 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1636618

Ogilvie, Marilyn B. and Choquettee, Clifford J. “Nettie Maria Stevens (1861-1912): Her Life and Contributions to Cytogenetics” the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 125, No. 4, August 1981

Comments are closed.

I really like the topic of this paper and I think what would make it especially compelling would be to include quotes from the men around these women. I could envision an analysis of those quotes similar to what you already have, but which would feel more concrete. I’m thinking that this would be an interesting longer paper, to examine what was said about these particular women, and explore what’s different (or not) among women in the sciences now.

I know in my own field, women have been faulted for not producing fast enough or as much as men, which tends to stunt their career. There has been a call to focus on quality not quantity, but of course, that requires more work to evaluate. The research is out there, so it might be something you’d be interested in looking at.